This summer I’ll be doing a handful of readings in Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine. Details below!

Huge Cloudy Book Launch/Walk

Full details on the Book Launch page of my site: https://www.billcarty.com/booklaunch

And thanks to Caroline Myers for this poster, which is perfect!

Huge Cloudy Now Available

Huge Cloudy is now available on the Octopus Books site. Lots of more info on the book landing page, including blurbs, reviews, and all that good stuff.

https://www.billcarty.com/huge-cloudy

This book begins in the weather and in a sense ends here, with this photo from Bresson:

Boston Review's Top 25 Poems of 2017

My poem "Not a Moat" was one of Boston Review's most read poems of 2017. Here's the full list of poets: http://bostonreview.net/poetry/boston-review-our-top-25-poems-2017

And I love this introductory note from editors Timothy Donnelly, BK Fischer, and Stefania Heim:

"The year in poems, like the year itself, marks episode after episode of dismaying breaches of justice and decency, even as it invites us into cul-de-sacs of wish, of wit and discernment, and of aching beauty. An end-of-year roundup of poems is often an occasion to stake a claim for why poetry matters, but it may be the case that it doesn’t, not the way we wish it did. Poems never have, and probably never will, measurably diminish the damage of floods, the slaughter of crowds, the incineration of forests, the assaults on dignity, or the exploitation of millions at the hands of the corrupt and rich. Yet week after week, the poets we have published have offered not answers or remedies but instants, instantiations of the power of the lived word as it unfolds for readers in real time."

Poem for the New Year in City Arts

The January issue of City Arts features an excerpt of a long poem titled "Bounding Sphere." I especially like how the poem is paired with Counsel Langley's artwork, "You Didn't Mean To Do That, Did You" (pictured below).

Art by Counsel Langley

Essay on A.E. Stallings

A.E. Stallings reads next week for the Seattle Arts and Lectures Poetry Series. In advance of her reading, I wrote this essay, "Close Entanglements," on her work (with some shout-outs to Lucretius, Mary Ruefle, and Velcro):

Three "Complicities" at Warscapes

I love the range of writing published at Warscapes, and it's an honor to have three poems published there: http://www.warscapes.com/poetry/three-complicities

Here's a sample:

TERRARIUM

Cat at the screen door.

Red mountain heather

cupping last daylight

in its bells. If we notice this

are we not barbarians?

Hare in the penumbra

safe from all but the owl.

We lay a glass bowl over it.

Now safe from everything

but the inside.

On Merwin's THE LICE

On September 24th I'll be leading a discussion at Open Books on W.S. Merwin's collection The Lice, recently released in a 50th anniversary edition by Copper Canyon. Here's a short preview of the discussion:

***

“Danger knows full well / That Caesar is more dangerous than he.” So says Caesar in the second act of Shakespeare’s play, knowing what’s true of himself is true for mankind more broadly. Substituting “humans” for “Caesar” in the above formulation, one approaches something of the prevailing mindset in W.S. Merwin’s collection The Lice. These are poems that often mirror creation mythology in their tone (“Animals I never saw / I with no voice / Remembering names to invent for them”), while adumbrating modes of uncreation. As humans, we have made of the earth “A small place / Where dying a sun rises.”

Earlier this summer, as Shakespeare’s Caesar—via New York’s Public Theater’s production—re-entered political discourse, I returned to the speaker of W.S. Merwin’s poem “Caesar,” who we find “Wheeling the president past banks of flowers / Past the feet of empty stairs / Hoping he’s dead.” As Adrienne Raphel observes, the leader here is both “tyrant and puppet,” and Merwin’s poem reminds us that the President (and all political power) is the product of both collective imagination and visceral violent devices. The poems in The Lice, first published in 1967, explore these realms of violence and imagination, person and politics, nature and human.

While the poems in The Lice occasionally touch on specific past events (the Vietnam War, JFK’s assassination), their cumulative impact feels prophetic. We see noble mythologies of war and peace unravel as the planet unravels: “One must always pretend something / Among the dying.” Grace, if allowed, is inhuman: “Tonight once more / I find a single prayer and it is not for men.” Among animals, one most beastly.

On one hand, it’s as the servant says to Caesar, passing news of the augury: “Plucking the entrails of an offering forth, / They could not find a heart within the beast.” But on the other, we have the force of language—not a consolation so much as an elucidation—within Merwin’s book: “If there is a place where this is the language may / It be my country.”

New Issue of Pinwheel Posted

The new issue of Pinwheel has some great poets in it, including Jaswinder Bolina, Terrell Jamal Terry, and translations of Diana Morán. The issue also includes my poems "Deer Stream" and "Vessel." Check the whole issue!

Photo by Sanja Marusic

"The Desired Change Will Occur" Broadside

Octopus Books made these pretty broadsides for a poem from Huge Cloudy for release at the final APRIL festival in Seattle. Now available here:

http://www.octopusbooks.net/books/desired-change-will-occur-broadside

"Disturbing the Peace"—Spring Class at Hugo House

Beginning April 20th I'll be teaching a class on politics and poetry at the Hugo House. A full description is here, and I'm excited to explore contemporary as well as historical examples, beginning with Virgil's Eclogues, in which the shepherds have a complex relationship to Roman politics, but an equal—and not unrelated—devotion to song. Below is an example, translated by Nate Klug in Rude Woods:

"Kings and complex battles–starting out,

I only liked a certain kind of song.

But then Apollo got me by the ear:

A shepherd should keep the flock fat

but his lines refined, like exquisite thread.

So now I woo a rustic muse on this compacted reed.

Don’t worry, General Varus, you’ll find plenty

of poets begging to construct your epics;

it’s simply that I no longer sing

what doesn’t simply come to me."

Emily Dickinson Award from Poetry Society of America

I'm honored and surprised to learn that Monica Youn chose my poem, "Silk Nor Say," for the Emily Dickinson Award as part of the Poetry Society of America's annual awards. Here is a link to the poem, and Youn's full citation below:

https://www.poetrysociety.org/psa/awards/annual/winners/2017/award_10/

“Ants, we are told, can lift 50 times their own body weight—something that doesn’t seem strange when you look at their chitinous exoskeletons, but that feels startling when you turn your attention to their hair-thin, cantilevered legs. Something of the tensile delicacy of an ant’s leg inheres in the poems of Emily Dickinson and in this poem, “Silk Nor Say”—a seemingly insubstantial attachment that is almost invisibly armored; a sudden acute angle that seems arbitrary until you realize how much weight it bears. Insectile weightlessness meets perpendicular gothic in the slant rhymes of the poem—asked / thicket/ knotted/ battled / better / reluctant / attention / butterfly / lightning / silent / secret – counterbalanced by luxuriantly drawn out monosyllables—cool / mind / blue / eye / gray / line. Sonics and sensibility merge here— you begin to experience the recursive folds of thought as a kind of rhyme, compulsive self-doubt as a kind of rhythm.”

Yannis Ritsos Discussion

This Sunday I'll be moderating a discussion on Yannis Ritsos's Diaries of Exile. Below is a blurb I wrote for the Open Books website:

***

An early entry in Yannis Ritsos’s Diaries of Exile begins, “Lots of things give us trouble. Lots.” Such directness is common in Ritsos’s work, yet in this collection, recounting his years as political prisoner during and after the Greek Civil War, Ritsos finds particular resistance and solidarity in daily action and observation. Throughout, Ritsos hints at the powerlessness of his position: “If we try to open a door / the wind shuts it.” “I want to compare a cloud / to a deer. / I can’t.” “I want to write Mitsos a poem / not with words / but with yellow lilies.” Yet for every instance in which poem-seems-not-enough, another glimpse at the quotidian arrives with the force of epiphany:

The three lighted windows

in the closed-up-house.

Was it ours once?

Everything is

like the light we miss.

In recent years, the island of Limnos, where Ritsos wrote the first two sections of Diaries of Exile, has been the landing point for a fair number of Europe-bound refugees. In one account, a farmer welcomed these new arrivals despite his neighbors’ wariness, explaining: “If they would have seen these people’s eyes, they would have changed their minds in a minute.” Ritsos’s writing is a similar—and timely—testament to the power of intimate vision versus political forces.

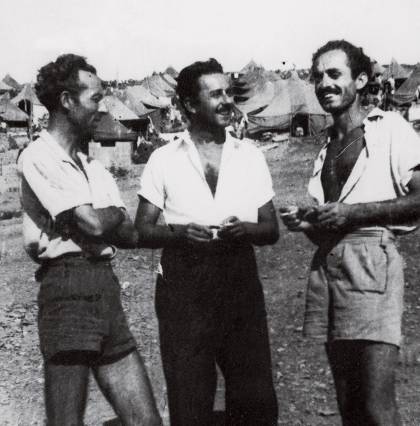

Ritsos (center) at Makronisos.